Welcome to Zimbabwe. The country that once led the world in providing free health care and education in the 1980s is now in trouble. The economy has stagnated, public services are failing and political tensions are mounting. The man in charge is old and increasingly frail. Last year, President Robert Mugabe spent US $50 million on trips to Singapore, 8000 km from home, for medical treatment. He routinely falls asleep at public events, though his spokesman says Mugabe is “resting his eyes.” He appears unable to resolve the civil war within his own party, in which one faction is led by his vice-president and the other by his wife, who is clearly angling to succeed him. Ministers and senior officials routinely insult each other on social media and in the government-owned newspapers. It’s become a circus.

Meanwhile, human rights violations are rife. Elections are scheduled for 2018 and allegations are already circulating that voter registration favours government sympathizers. As the ruling ZANU-PF party’s traditional coalition of supporters crumbles, the state is lashing out at opponents. A large group of the liberation war veterans, a traditional pillar of support for Mugabe’s party, have now defected. Their leaders have been harassed, jailed and placed under surveillance for having the temerity to call for free and fair elections – and for having denounced the First Lady’s pretensions to dynastic rule. As Mugabe deteriorates, if not teeters, Zimbabwe’s political elites are positioning themselves for the inevitable transition that will follow.

The outside world, too, should be preparing for the consequences of Mugabe’s demise. Zimbabwe’s neighbours, notably South Africa, will bear the brunt. Preventive diplomacy should be the immediate priority – while planning for a full-scale humanitarian crisis. This would be a change from the usual practice of ignoring the clear signs and risks, only to react once the long lasting strongmen eventually, “suddenly,” depart.

There has long been a naïve view in western publics and policy circles which holds that the problem with Iraq was Saddam Hussein, that Libya would be better off without Moammar Gadhafi, and that Mobutu Sese Seko’s departure would herald a bright future for Zaïre. The solution? Get rid of the strongman and democracy will naturally follow!

It isn’t the case. The fall of a longstanding authoritarian leader typically leads to one of two sub-optimal outcomes: regime continuity (e.g. Cuba, North Korea, Togo, Turkmenistan) or state collapse and protracted civil conflict (e.g. Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Zaïre/Democratic Republic of the Congo). While many different factors are present in each case, two usually play determining roles: the cohesiveness of national elites and the role of the international community (especially neighbouring states).

In Zimbabwe today, elite cohesiveness is lacking and, hence, all the signs point to a disorderly succession. The ruling party is in or close to civil war. Former ZANU-PF supporters in the war veterans and in the faction of the party expelled in 2014 with then vice-president Joyce Mujuru are waiting to see what kind of ZANU-PF emerges after Mugabe goes. Opposition political parties are trying to form a coalition to challenge Mugabe and ZANU-PF in the 2018 elections, but the success of that venture is far from assured. The opposition parties have a long history of factionalism.

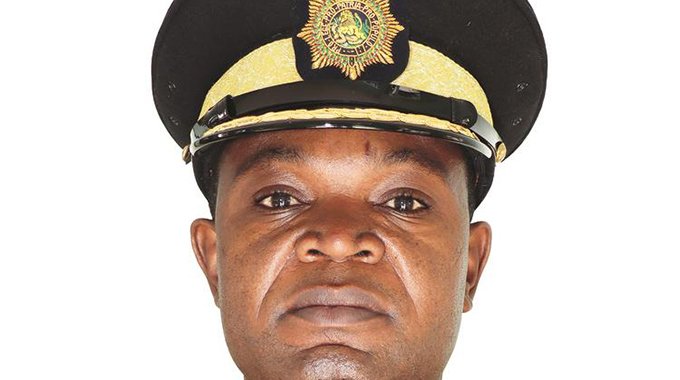

The role played by the security forces will be important, since they have been a bulwark of ZANU-PF rule. Military leaders have at times publicly denounced opposition politicians, saying they would not allow such people to take power, even if elected. Zimbabwean civil society is active and brave in defending human rights and the rule of law, but faces an entrenched bureaucracy, partisan state-owned media, and the hardline security establishment; all these are hostile to robust democracy.

That leaves the international community. The neighbouring countries, especially South Africa, will not intervene unless asked by Zimbabwe, or unless a full-blown crisis erupts, as one did in 2008-09. Having learned from their hubris and incompetence in Iraq and Libya, the Western powers’ taste for regime change is much reduced. Those Western powers have also lost interest in Zimbabwe over the last decade, distracted by challenges in the Middle East and at home. Their fierce denunciations of Zimbabwe’s 2000-03 land reform are now a distant memory. The Western power with the deepest connection to Zimbabwe, the United Kingdom, is absorbed with the self-inflicted wound of Brexit and has little time for its former colony. As for the United Nations, the Security Council is overwhelmed and divided by other conflicts.

In short, a serious breakdown of political and civil order in Zimbabwe is likely, along with attendant human rights abuses and even a humanitarian crisis. It is coming soon, as friends and foes alike realize that Robert Mugabe cannot last forever. Zimbabwean politicians are not the only ones who need to plan for his departure. The question is, who in the international community will step up and lead an effort to prevent or mitigate the impending meltdown in Zimbabwe, or even to plan for dealing with the fallout?

Lauchlan T. Munro is an associate professor in the Faculty of Social Sciences and John Packer is an associate professor in the Faculty of Law, both at the University of Ottawa.